OddVoices Dev Log 1: Hello World!

The free and open source singing synthesizer landscape has a few projects worth checking out, such as Sinsy, eCantorix, meSing, and MAGE. While each one has its own unique voice and there’s no such thing as a bad speech or singing synthesizer, I looked into all of them and more and couldn’t find a satisfactory one for my musical needs.

So, I’m happy to announce OddVoices, my own free and open source singing synthesizer based on diphone concatenation. It comes with two English voices, with more on the way. If you’re not some kind of nerd who uses the command line, check out OddVoices Web, a Web interface I built for it with WebAssembly. Just upload a MIDI file and write some lyrics and you’ll have a WAV file in your browser.

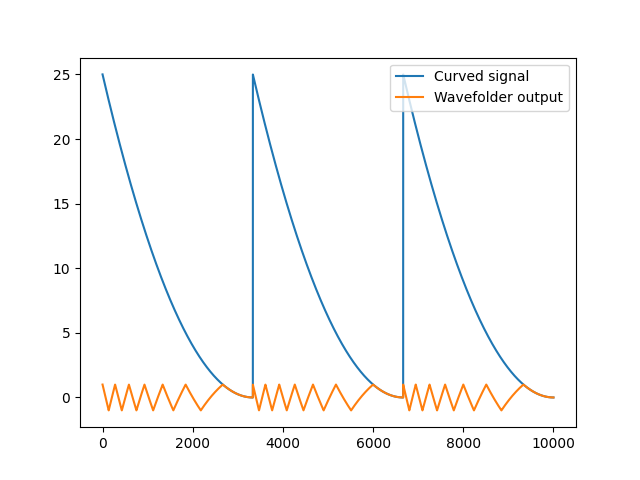

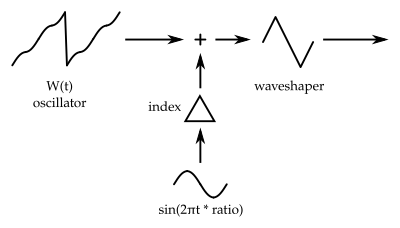

OddVoices is based on MBR-PSOLA, which stands for Multi-Band Resynthesis Pitch Synchronous Overlap Add. PSOLA is a granular synthesis-based algorithm for playback of monophonic sounds such that the time, formant, and pitch axes can be manipulated independently. The MBR part is a slight modification to PSOLA that prevents unwanted phase cancellation when crossfading between concatenated samples, and solves other problems too. For more detail, check out papers from the MBROLA project. The MBROLA codebase itself has some tech and licensing issues I won’t get into, but the algorithm is perfect for what I want in a singing synth. Note that OddVoices doesn’t interface with MBROLA.

I’ll use this post to discuss some of the more interesting challenges I had to work on in the course of the project so far. This is the first in a series of posts I will be making about the technical side of OddVoices.

Vowel mergers

OddVoices currently only supports General American English (GA), or more specifically the varieties of English that I and the singers speak. I hope in the future that I can correct this bias by including other languages and other dialects of English.

When assembling the list of phonemes, the cot-caught merger immediately came up. I decided to merge them, and make /O/ and /A/ aliases except for /Or/ and /Ar/ (here using X-SAMPA). To reduce the number of phonemes and therefore phoneme combinations, I represent /Or/ internally as /oUr/.

A more interesting merger concerns the problem of the schwa. In English, the schwa is used to represent an unstressed syllable, but the actual phonetics of that syllable can vary wildly. In singing, a syllable that would be unstressed in spoken English can be drawn out for multiple seconds and become stressed. The schwa isn’t actually sung in these cases, and is replaced with another phoneme. As one of the singers put it, “the schwa is a big lie.”

This matters when working with the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary, which I’m using for pronouncing text. Take a word like “imitate” – the second syllable is unstressed, and the CMUDict transcribes it as a schwa. But when sung, it’s more like /I/. This is simply a limitation of the CMUDict that I don’t have a good solution for. In the end I merge /@/ with /V/, since the two are closely related in GA. Similarly, /3`/ and /@`/ are merged, and the CMUDict doesn’t even distinguish those.

Real-time vs. semi-real-time operation

A special advantage of OddVoices over alternative offerings is that it’s built from scratch to work in real time. That means that it can become a UGen for platforms like SuperCollider and Pure Data, or even a VST plugin in the far future. I have a SuperCollider UGen in the works, but there’s some tricky engineering work involving communication between RT and NRT threads that I haven’t tackled yet. Stay tuned.

There is a huge caveat to real time operation: singers don’t operate in perfect real time! To see why, imagine the lyrics “rice cake,” sung with two half notes. The final /s/ in “rice” has to happen before the initial /k/ in “cake,” and the latter happens right on the third beat, so the singer has to anticipate the third beat with the consonant /s/. But in MIDI and real-time keyboard playing, there is no way to predict when the note off will happen until the third beat has already arrived.

VOCALOID handles this by being its own DAW with a built-in sequencer, so it can look ahead as much as it needs. chipspeech and Alter/Ego work in real time. In their user guides, they ask the user to shorten every MIDI note to around 50%-75% of its length to accommodate final consonant clusters. If this is not done, a phenomenon I call “lyric drift” happens and the lyrics misalign from the notes.

OddVoices supports two possible modes: true real-time mode and semi-real-time mode. In true real-time mode, we don’t know the durations of notes, so we trigger the final consonant cluster on a note off. Like chipspeech and Alter/Ego, this requires manual shortening of notes to prevent lyric drift. Alternatively, OddVoices supports a semi-real-time mode where every note on is accompanied by the duration of the note. This way OddVoices can predict the timing of the final consonant cluster, but still operate in otherwise real-time.

Semi-real-time mode is used in OddVoices’ MIDI frontend, and can also be used in powerful sequencing environments like SC and Pd by sending a “note length” signal along with the note on trigger. I think it’s a nice compromise between the constraints of real-time and the omniscience of non-real-time.

Syllable compression

After I implemented semi-real-time mode, another problem remained that reared its head in fast singing passages. This happens when, say, the lyric “rice cake” is sung very quickly, and the diphones _r raI aIs (here using X-SAMPA notation), when concatenated, will be longer than the note length. The result is more lyric drift – the notes and the lyrics diverge.

The fix for this was to peek ahead in the diphone queue and find the end of the final consonant cluster, then add up all the segment lengths from the beginning to that point. This is how long the entire syllable would last. This is then compared to the note length, and if it is longer, the playback speed is increased for that syllable to compensate. In short, consonants have to be spoken quickly in order to fit in quickly sung passages.

The result is still not entirely satisfactory to my ears, and I plan to improve it in future versions of the software. Syllable compression is of course only available in semi-real-time mode.

Syllable compression is evidence that fast singing is phonetically quite different from slow singing, and perhaps more comparable to speech.

Stray thoughts

This is my second time using Emscripten and WebAssembly in a project, and I find it an overall pleasant technology to work with (especially with embind for C++ bindings). I did run into an obstacle, however, which was that I couldn’t figure out how to compile libsndfile to WASM. The only feature I needed was writing a 16-bit mono WAV file, so I dropped libsndfile and wrote my own code for that.

I was surprised by the compactness of this project so far. The real-time C++ code adds up to 1,400 lines, and the Python offline analysis code only 600.